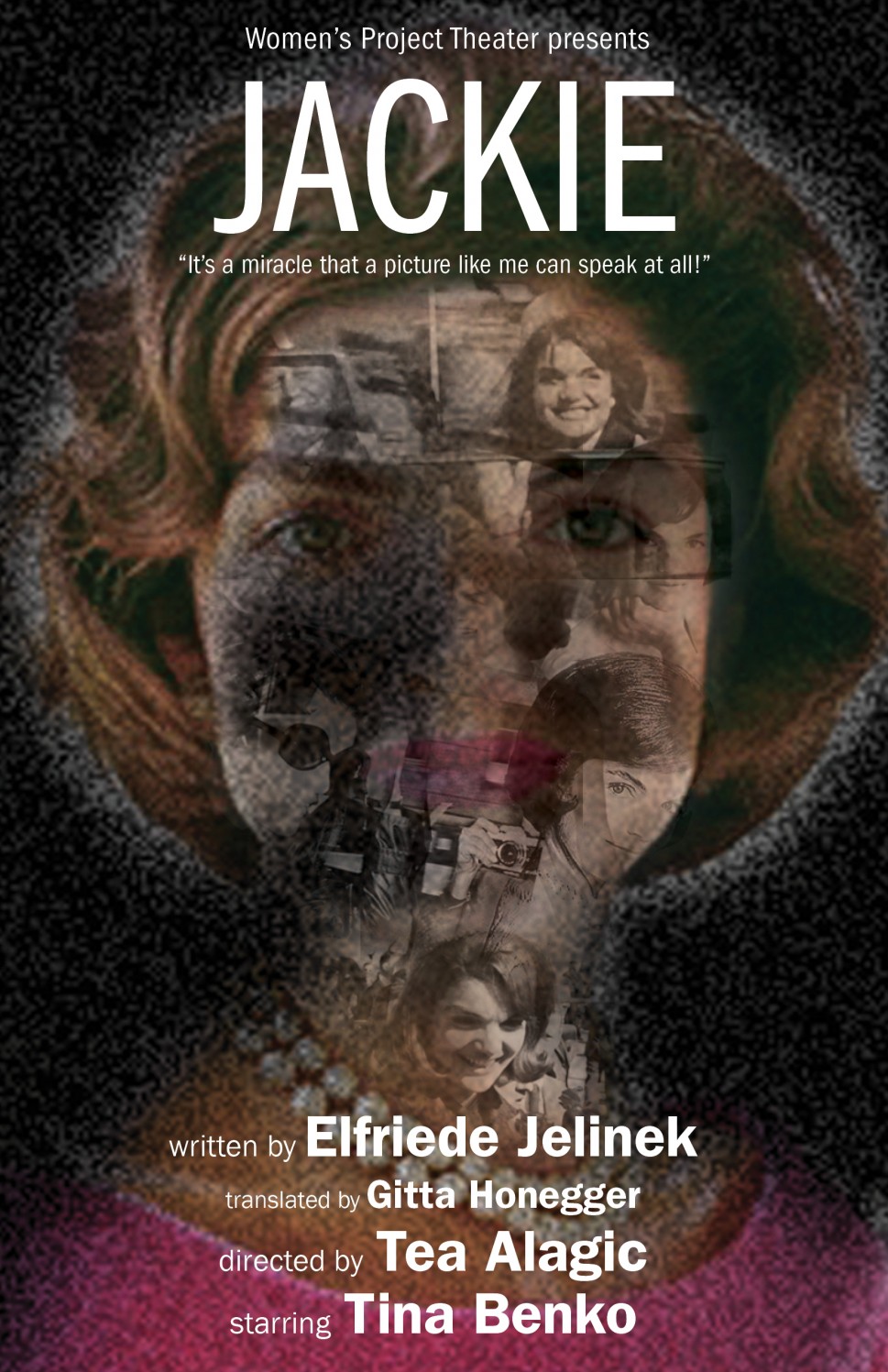

It is rare that NYC audiences get a chance to experience the intricate, idiosyncratic writing of Austrian Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek – best known from M. Haneke’s film The Piano Teacher. This March the Women’s Project Theater is bringing the North American premiere of Jelinek’s JACKIE, “an intensely theatrical dissection of Jackie Kennedy Onassis and the myths surrounding her well-coiffed veneer”. Translated by Gitta Honegger, directed by Tea Alagic and starring Tina Benko, the play starts previews on February 24th and opens on March 5th until the 31st at City Center Stage II. Below is an excerpt of an exclusive interview with Gitta Honegger (who will also be appearing in panels at CUNY and ACF to discuss the translation and staging of the play) discussing JACKIE and the writing of Elfriede Jelinkek. The full interview by Alexis Clements is available here.

AC: […] Some of [Jelinek’s] work can be very challenging, particularly in the novel form. You have to make a commitment as a reader of her work to put forth a bit of effort. But theater allows the work to be seen in different lights, to be interpreted by other artists. Do you think seeing her work in the theater helps people who otherwise might find it difficult to engage with her writing on the page?

GH: Well, you know,her writing is also quite funny. But either you accept her directors’ often experimental approaches or you don’t. She encourages directors to translate her work into their very own visual language and she doesn’t interfere with that. So, you have to go along with their vision. And not all audiences go for it. What she does get is a lot of young people. I’m amazed at the youth of the audience, when I see productions of her plays, I often see her shows more than once, and young people totally relate to her in Germany and in Austria. And then, of course, you have the women of our generation.

AC: Let’s talk more about her play Jackie specifically. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis is something of a specter in American culture. Certainly, at the very least, every first lady since John Kennedy’s presidency has had to reconcile their relationship to her legacy. And she’s obviously also a big part of the ongoing cultural obsession with John Kennedy, as well as the increasing connection between celebrity and politics in this country. To your mind, why look again at this woman who has been so discussed and dissected over the decades, through the lens of Jelinek’s writing?

GH: Well, it’s part of Elfriede’s cycle of Princess Plays. She describes them as a satirical counterpoint to Shakespeare’s histories, which in German are called “Kings Plays.” She has Snow White and Sleeping Beauty and Princess Di—it’s actually one big play. And you couldn’t leave out Jackie Kennedy—for the 20th Century she is the essential princess. Also, [Jackie Kennedy] was so closely identified in Europe as the first one to bring culture to the White House. I mean that wasn’t her motivation, but that’s the image of her in Europe.

AC: Picking up on of some of what we talked about before, in terms of the idealized version of America, do you think there’s something interesting about having Jelinek’s perspective on an American icon as an outsider to the country?

GH: Well, you know, I’m not sure that it’s that different, because it’s all mediated reality. In America we are so used to looking at America through the media, and I think the average American, most probably, doesn’t know their royalty either, except through the media. Elfriede’s not trying to go into any biography or psychology, she’s really constructing and de-constructing a mediated image. I think that’s the hardest, ultimately, to get across.

AC: That touches on one of the things that I think is so interesting about this play and other works by Jelinek. There’s a tension in many of her characters between the expectations from outside and the desire of the individual on the inside, specifically the places where the expectations and desires clash. In the case of Jackie, it’s the larger culture, politics, and media imposing upon a real human being who remains subsumed beneath all those things. But in other works, The Piano Teacher, for instance, which for most American audiences is their primary contact with Jelinek, it’s the mother’s expectations of the daughter. In Jackie, as you indicate, Jelinek isn’t attempting to represent the real human being Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, but it so clearly demonstrates everything that was imposed on that person, who was in many ways trapped by those impositions. You have a much wider view of Jelinek’s body of work—do you have a sense of that tension existing in other works of hers?

GH: Well, I think you really got it, and specifically, it does go back to the mother, and that feeling—the expectations. I think that’s at the core—the expectations and the performance you do to meet the expectations. I would say that’s the driving force in Elfriede. […]