This final round-up for work from the Camden People’s Theatre Sprint Festival features interactive and participatory work. The festival featured a rich selection of audience involvement this year, with everything from video game testing to walking tours.

Place and Means’ Good Riddance

This delightfully madcap walking tour is presented by Place and Means. Both the Tour Guide and his assistant Ari (short for Ariadne, that character from Greek mythology who helped Theseus through the labyrinth) have their own agenda for this tour. In moments where they’ve distracted their co-guide, they warn you to look out for clues they’ve hidden along the path. They made a delightful odd couple: the Tour Guide urging you to stop and smell the roses (one of his hidden notes says, “Take a moment to look at the sky. Isn’t it lovely?”), with Ari barking out reminders to stay together and take care when crossing streets. Clues come together about Ari’s questionable past, and questions are raised about the Tour Guide’s role in her history. Guests asking about the historical significance of landmarks may be disappointed (“That tree is made of wood, I can tell you that.”), but nosing into your guides’ history is rewarded with tantalizing tidbits of the story. Each audience member’s experience is different based on which clues they find along the way, and who asks what question. Though the whole narrative never became completely clear, it mattered not a jot; as with any tour, the fun was in the journey rather than the destination.

2 Magpies’ The Litvenenko Project

2 Magpies Theatre, Nottingham-based company that creates site-responsive new work brings their Litvenenko Project to the Camden People’s Theatre. This immersive piece, set in the bar/café area of the theatre, follows the trail of Alexander Litvenenko, an ex-Russian spy, on the day in 2006 that he was poisoned by polonium in his tea. Performers Tom Barnes and Matt Wilkes chat to audience while serving tea before the show to find out what they know or remember about the case. Many of these tidbits are incorporated during the performance. Each event in Litvenenko’s journey is paired with an apt visual metaphor. There’s a coffee cup mounted on top of a broom handle and tipped back and forth between the two actors as Litvenenko is bounced between two old friends. Football team scarves are used to puppeteer the actor playing Litvenenko as he’s persuaded to drink cup after cup of tea. Red yarn is used to trace the path of the polonium contamination. And there’s a truly memorable sequence involving hazmat suits and a raw chicken. Even for those who know nothing about Litvenenko’s story, this piece provides a thoughtful insight into a still-unsolved crime.

Josh Coates’ Particles

Josh Coates’s engaging, disarming style of storytelling draws the audience into his world and invites you to go with him on a journey that might end in any number of ways. The evening takes the form of a repeating story that changes with small decisions. A phone rings, pick it up or don’t, who’s on the other end, how do you respond. Coates lets his audience in on the decision-making process at points, though this is a gentle, pleasantly low-key process. “I’m going to do the audience participation bit now,” Coates announces. What distinguishes his way of interacting from most terror-inducing instances of a performer dragging some poor sod up on stage is that he takes excellent care of his audience. “Would you mind joining me on stage for a minute?” he asks. “You don’t have to.” And later, after an audience-participant fumbles: “Sorry, I didn’t make that clear.” This results in some delightful contributions to the story, such as three audience members screaming and throwing bits of paper at each other as we’re told about a post-apocalyptic riot. The piece covers everything from the origins of the universe to the end of the world with humor and no little beauty. “When do you think the world will end, and what would you change, knowing that?” Coates asks. In the end, recordings of answers to those questions play from a small recorder in the dark space while Coates opens windows that let in the orange glow of a London night.

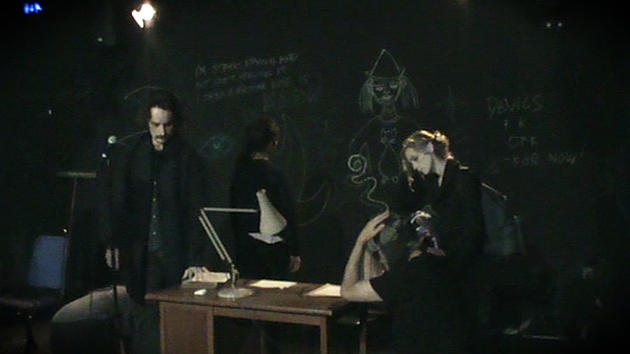

Dirty Market’s Black Box

Dirty Market call themselves bricoleurs, and for this event, they brought together a short story, an audience, and a simple set of rules. After reading a story, audience members were encouraged to pull a card from a deck, each of which laid out a prompt for an action. Like an acting class on improvisation, participants played and interacted. Shier folks were provided with “audience” cards that didn’t require performing, but rather listed a provocation, e.g. “imagine hugging someone for a very long time.” Apparently some audience members had engaged in pre-show preparation and development of the piece, but the whys, wheres, and hows of that were never explained. The chaos resulted in some interesting moments. For example, a man stood in front of a microphone and spoke about good things that had happened to him in the past week, while another participant called encouragement. However, the freedom to follow instructions among strangers with no guidance can also be precarious, as I noticed several participants facing uncomfortable moments with overenthusiastic partners.

Beta Public

Beta Public, the fourth in a series of nights curated by Tom Martin and Pat Ashe, presents both video games and performances for an intriguing mash-up of liveness, interactivity, and the virtual. In honor of the Sprint Festival, entries were loosely themed around sports, speed, or short duration. In the first half of the evening, participants were set loose on a building full of video games in various stages of development.

- In Andi McClure & Michael Brough’s Become a Great Artist in Just 10 Seconds, key-mashing might result in some impressively plausible modern art.

- For Steel Crate Game’s Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, one player dons Occulus Rift virtual reality goggles and tries to defuse a bomb, with help from other players who are reading from a printed manual.

- Michael Molinari’s Choice Chamber allows the audience to make choices that affect the player (for example, what weapon he’ll receive). Due to some technical difficulties, the computer was making the choices on the night, but nevertheless, the idea of harnessing spectator’s opinions to affect gameplay was intriguing.

The second half of the evening presented three short performances of in-process work. First, game designer and theatre maker Hannah Nicklin performed a section of her work Equations for a Moving Body. She talks about training for an Ironman race, and going on runs with her friend, who recently passed away in a climbing accident a few years back. The facts in this section are cleverly revealed in the same way we learn most things nowadays: by opening several tabs on an internet browser. The sections she presented wove together beautifully to become more than just isolated anecdotes about sport. Next up, William Drew read a meditation on loss and technology, musing over how we remember dead people on Facebook. It’s themes happened to resonate nicely with Nicklin’s performance. Finally, Tassos Stevens of Coney, played the audience through a bit of Run, Sally Run. This gamified performance is part of a Coney project, Codename: Remote. The audience makes choices about the narrative by voting: hold up your card for one option, leave it down for another. In this system, there’s no way to avoid registering a vote.