As a vector of performance, participation has risen in prominence over the last fifty to sixty years to become one of the key concepts in contemporary performance practices. Ant Hampton exemplifies an approach to participation that depends on subtlety, rigor, and imagination. In 2007 he and Silvia Mercuriali were working together as Rotozaza when they coined the term autoteatro. From Rotozaza’s website:

The Autoteatro series, which began in 2007 with Rotozaza’s ‘Etiquette’, explores a new kind of performance whereby audience members perform the piece themselves, usually for each other. Participants are given instruction via audio, visual cues or text for what to do or say. By simply following these instructions an event begins to unfold. Not to be confused with gaming (or ‘game show’-like improvisation), Autoteatro does not ask audience members to be clever or inventive, neither does it set up instances of competition. It’s also possible to define it as

- not involving any ‘audience’ beyond the participants themselves

- functioning automatically: there are no actors or human input during the work other than the participants. An Autoteatro work is a ‘trigger’ for a subsequently self-generating performance.

Since Rotozaza stopped producing work in 2009, Hampton’s work has explored the affective dynamics of social and architectural space through a series of pieces that make sensible submerged or suppressed relationships and histories. His newest work, The Extra People, performs as part of the Crossing the Line Festival at FIAF in New York City September 25-26.

I was fortunate to sit down with Ant last February just after his developmental residency for The Extra People at EMPAC. Among other topics, we discussed the role of representation in his work, the influence on his work of his training as a physical theatre performer, and the liberating potential of shouting while being forcibly ejected from a gallery.

Ben Gansky I’d like first to ask about the role of representation in your work and in forms that like autoteatro are, let’s say, purely participatory and seem to suppress entirely the element of spectatorship. If we’re imagining a spectrum of this factor in performance, is it fair to locate autoteatro at the far end of the spectrum away from representational kinds of work?

Ant Hampton Yeah, I don’t know. I feel like I’ve seen performance work which is less representational [than autoteatro]. It depends on which [piece] you’re talking about. Some of them more than others. Like in Etiquette there’s lots of representation, there’s lots of imagining other places. Even in The Quiet Volume there’s a lot. I mean, different kinds of representation going on there.

The Quiet Volume is in a way starting from a point of looking at the potential of being taken away, through writing. I mean, because of the [Rimini Protokoll’s] Parallel Cities context of the commission I had this interest in thinking about library stations as places of departure, somewhat akin to stations. I think I thought about that for a while; nobody goes to a station to stay there, similarly to a library. Everyone there is going there to get somewhere else, if not physically. So it’s a kind of representation, of saying for a moment, ‘imagine not being here’ or imagine other things. But with OK OK which is this four person speaking thing, one of the rules that we only break, like massively, at the end, is there’s no representation, at all. Except for this main conceit that is like a very, very thin scrim of representation, which is the text sort of second-guessing everything that you’re thinking. And the situation that you’re in, what you think might be coming next. It’s constantly playing that game.

It’s no images at all. At one point someone says, well, at least we’re all in the same boat, and that causes problems. Like someone says, wait a minute, is this supposed to be a boat? [laughs] And they’re like no, no, no, it’s a figure of speech.

So, whereas when I think about really hardcore performance art that is non-representational at all, it’s just like someone doing stuff in front of you. In a way, it’s quite easy to completely eschew representation. I guess it’s more a question of how it’s treated, and whether it’s taken seriously and so on. I mean, there’s the whole post-dramatic theatre idea, and I sort of feel like yeah, a lot of the autotheatre stuff fits into that discourse quite easily. Because it’s more you know, questioning the means of representation and the processes by which we watch and are aware or not of what’s going on. But it’s constantly playing with representation. Like I said earlier, setting it up in order to break it down. Setting it up in order to cut the strings and feel it fall.

In a way it’s in the fall I think more than anything else… I never watched a lot of TV, but when I was in a moment of crisis I think around age 20, I knew that my life was potentially in a ‘fall’ situation and I would kind of watch TV and forget all about that fact for a moment. And when I would turn the TV off, I would feel the reality of my world kind of come crashing down again. And it was, you know, very unpleasant at the time but it made me aware of how this fall from other worlds back into the real one is very palpable and kind of defines us a lot nowadays.

BG Even moreso perhaps than just watching TV, we have all these screens in our pockets, in our hands, etc, it’s as though we’re constantly in this transit.

AH I don’t feel like I have any lack of screens in my life. TV is just one less. I mean… it’s important to try to keep in touch with what peoples’ realities are, if that’s even possible.

BG I’m curious about who for you is a significant antecedent to this work either in a performance tradition, or Fluxus, Yoko Ono, instruction pieces…

AH I mean… to be honest, I didn’t really know much about Fluxus or any of these score-based things prior to starting to make the work that I do. So yeah, if anything it would be retrospective. And I’m interested in them. I think where the inspiration really comes from is not so direct. There’s not really anybody that I can think of that I would say is an inspiration directly in that way. Not even really Janet Cardiff, although I always really loved her work. For me it was always something clearly different. Like when you’re on your own, it’s a completely different thing than what for me is autotheatre. That’s why Lest We See Where We Are, that piece is a real anomaly in a way, in the whole thing. I still think of it as that because it’s so self-reflexive, that it practically makes of you the other performance against which you measure yourself. And with the use of this prosthetic voice in the piece, there’s a sort of doubling of presence which makes the thing.

No, the inspirations for me come more obliquely. Or directly in terms of discourse and so on. You know, Tim [Etchells] was always a major influence, as I think for many others. In the way that his work, and of course Forced Entertainment opened up a whole set of other possibilities.

BG What was it about his work?

AT Well, it was a combination of his work and then the writing about his work that he would do, as well as other people’s. I think specifically, you know, it’s such a sort of basic thing now, but it was so important when I was starting out to have it confirmed that there is a difference between spectating and being a witness for instance. And that you can engineer that change in your audience. You can insist on it. You can give up, and let them fall back into being spectators again. And then between him and Jerome Bel as well. There’s a key bit of writing by Tim about Jerome Bel’s The Show Must Go On which also I remember crystallizing a lot of things, or kind of confirming a lot of things that I was discovering myself, to do with a balance of power, say, on the stage. What happens when you make something that’s so at risk on stage, and so fragile in a way, that the audience is sort of made aware that they [the performers] are no longer dominating the thing. For me, there’s always been an element of that, right from the beginning. When I made this piece [Bloke] where the guy on stage was clearly not a performer and was clearly just following instructions live, doing it as best he can, and everyone was hearing the voice at the same time as him, you know that you’re discovering everything at the same time as him. You put yourself in his shoes in a very real way. Like, what would I do in that situation. And as Tim says, you’re bound up with things in a sort of fundamentally ethical way. Which is very different from just the usual spectating.

So these are the real basic things that started me off. Or again, gave me the confidence and the curiosity to look further into that. Made me realize in fact that there was even such a thing as a performance tradition, and I was in it, somewhat. I sort of landed myself in it.

BG What kind of work were you making previous to Bloke?

AH Previous to that, it was actually also playing a lot with being in the room versus being somewhere else. The first two Rotozaza plays (Bloke was the third) were both in some way really playing that line. But it was coming from more of a theatrical background. I came out of theatre school in Paris, and made some work with friends. And then met Silvia in Milan and started making site-specific work in squats. But yeah, it was a lot of the time playing with, do we acknowledge the audience or not. How do we imagine their presence, what do we do with that. It was always, I was always really enjoying being as mischievous as possible in a way. Trying to work it as deliciously as possible. At the time I was also thinking of it as site-specific but I was also thinking of it as person-specific, actually. Writing things for people that only they could do.

In a sense then it became a lot about the act of doing that thing, and how that resonated. I was never really interested in telling stories or representation in that sense. Certainly interested in narrative all the time, and how you stitch together events. But the work was fragmentary, and person-specific, site-specific, also music-specific. Sort of writing around pieces of music. But it was the writing for people—

BG Would it be fair to say that it was focused on presence?

AH Yeah, I would say that. I was slowly sort of finding my way really. But I was not coming from an academic background. Certainly not at that point a visual arts background. So I really didn’t know much about anything like Fluxus or that kind of thing until later.

BG It makes sense to me to hear that you have a physical performance background, because I think that a lot of your work is indicating a deep understanding of the way that physicality evokes emotions, on an automatic basis. Physicality being key to affective response.

AH Yeah, I think so. For me for sure. It’s funny, because in contemporary performance or whatever that is, in the sort of Forced Entertainment lovers of this world, Lecoq is a bit of a joke. Because it’s very widely misunderstood. I think the reasons for that are because there a lot of companies out there who sort of take the surface appeal… there’s a sort of first degree of Lecoq. Which manifests itself as a kind of style. And there are companies out there with that style, let’s say. And they have their own appeal, but it’s not necessarily particularly wide. But then there’s like many other practitioners that come from there that are going into visual arts and all sorts of other things. Also, not acting but directing, writing, so on. I don’t really know about the wider diaspora of Lecoq. But I do know that lots of the teaching was very brilliant. There was as much thought going into pedagogy as there was into analysis of movement or any of the other elements of the school.

It’s true what you’re saying in the sense that, watching people from the outside doing Etiquette right now, which is quite unusual for me, sort of made me realize, or reminded me, of a lot of teaching in Lecoq. Some of this analysis of movement stuff was astonishing to me to learn about. For example, just small things like, I remember talking about like breathing, and how that’s something that actors forget a lot to do. In fact, one of the things that defines a good actor from a bad actor is whether or not they’re remembering to breathe. And then you’ve got the kind of actor who choreographs breathing into what they’re doing. Who knows when the breath is taken and when it’s not, and really what you’re doing with breathing. And so we would started looking at, just a few of the things. Like let’s see the difference between turning ninety degrees, seeing someone, and then breathing in, and taking a step towards them. And taking a breath in, turning ninety degrees, and taking a step towards someone. Or, taking a breath in, seeing someone, and then breathing out and taking a step towards them. It just, it gives totally different things. And it’s so fun for me to give instructions for something even as stupid as telling people the order in which to do something like that. And then finding yourself, finding that meaning falling into place as you’re doing it, or after you’ve done it. You do it, and then there’s this weight of expressivity that permeates out from you. And you’re like, my god, I didn’t realize that that was going to do that.

So in a way, it’s sort of like a reverse theatricality. It’s a self-theatricality.

BG It seems to be entirely spontaneous in a way that you couldn’t plan if you tried, where actually that sensation is arising from being entirely contrived.

AH Exactly. So I think what you mentioned earlier about representation, I mean it’s all there, representationally, but it’s more just a willingness to embrace artifice to get the job done in a way. Or, embracing artifice in terms of what forms part of the experience. It’s not about hiding those nuts and bolts, it’s about playing with them, sort of transparently, in the process.

But you know, there’s a point at which it’s hard to generalize any more, because like I say, all the works are very different, primarily because they’re all made with different collaborators. I do collaborate a lot with different people. Tim [Etchells] will bring something completely different to the work than Glen [Neath].

BG Do you have the sites before the collaborator, or do you pitch a project…?

AH Again, that’s also very different, like with The Quiet Volume there was the idea already in my notebooks, way back, just after doing Bloke, like there was for Etiquette, I had this idea that theoretically there could be a book which was in some way a show, like when you turn the pages it’s telling you to do things. It doesn’t actually remain in the reading, it’s actually giving you instructions to do things for real in the room, like turn on that light there, and now look at your hand, and now plug your ear with your left finger… (laughs) I don’t know, for example. And there were these notebooks that I had.

BG It seems that this is blurring the line between representation and the real thing, like you’re not saying, imagine pressing your hand.

AH Well, that you do for real in the library, you press your hand into the real thing, but then you’re imagining it falling through the page. Which usually doesn’t happen. (laughs) But then with The Quiet Volume, more and more I was reading Tim’s stuff, talking about text, his thoughts regarding text and writing, particularly what he wrote about how reading can in some ways parallel a sort of dramaturgical process. In that as you turn pages and read, there’s an unfolding event over time, and there’s a conjuring of presence. And the more I was reading about that, he was articulating it so beautifully, I thought ok, we should really be doing this project together. And that was around the same time that I met Stefan [Kaegi] and Lola [Arias], and they were conceiving of their Parallel Cities project. And so we were at a swimming pool, and I remember Lola mentioned this and I said, well, actually I’ve got a thing for libraries, and they said wow, well we should talk. (Laughs) That all fell together. So that’s how that collaboration started with Tim, although we’d known each other and worked together a lot on other smaller projects. A lot of the time I was kind of contributing things to something that he was doing. We did a whole fake program of performance as protest at the closure of the live arts program at the ICA. And then we were invited back to do it for real. Or not to do that for real, but something similar, an event to kind of open the doors again for that scene.

BG How did you end up meeting Tim?

AH We just kept on bumping into each other. And obviously, I went to see a Forced Entertainment show, that’s how I got to know of him. But something very different would be for example Glen [Neath]. I loved his writing, I had seen in the kind of Shunt cabarets in London. And I did an experiment, shortly after Bloke, with two people. So, I gave both of them headphones and started two CD players at the same time. CDs. Discmans, Discmen. And that was like a silly sketch with just some randomly generated material that I did, but it was fun, and it went on for about ten minutes or something. And after that, he approached me, and we had a drink for the first time, and we spoke, and he said, I would love at some point to talk about writing something for that setup, for two people on headphones. And I said it would be great to talk about it, let’s set a time. So we arranged to meet two and half weeks later in a pub. And I met him in the pub two and a half weeks later and I said yeah, it would be great to maybe, if you wrote something for this. And he said, well actually I already have, and he put down this big script on the table. In that time he’d already gone ahead and done it. And I’d say 90% of that script is today what exists as Rom-Com, which is a piece for stage, with two actors performing this romantic comedy. I don’t know, 90%… then I added a lot in terms of the staging of it, the physicality, instructions for doing stuff, and then Britt [Hazius], my partner, she’s an artist in her own right, she did the whole backdrop, which was also the lighting for the show, and also the whole soundtrack as well. So that was a completely different kind of collaboration. He’s a writer, a playwright, but with an expanded outlook on things.

BG We alluded briefly earlier to Claire Bishop’s critique of socially-engaged, socially-situated art. I think certainly in the last 10 or 15 years the footprint for participation-based work has become huge. And a lot of the pieces that get talked about in that framework are big projects, like Pawel Altheimer, Tania Bruegera, Pablo Helguera, etc, artists that are making platforms for the participation of hundreds if not thousands of people to have long engagements. I find that your work occupies this other end of the spectrum, which is about a highly choreographed, very specific and personal experience, with this very granular control over the event. I wonder what you think about the conceptual bases of these participations, what you think the political content is, if anything.

AH Again, this varies so much from piece to piece, also in its intention. It’s something I’ve been more and more interested in. Last year I worked with Edit Kaldor, we worked for almost a year preparing it, and then delivered a ten week block for some MA students at DasArts in Amsterdam. A block is where they invite artists in to design what they call a series of significant collisions for the students there. That might involve us inviting other artists in to give assignments or so on, or actually traveling somewhere. And we decided to make it about the extent to which you can plan and engineer specific impacts with what you make. Basically, asking the question, what can art do? Or is that really not something that… we were met with a lot of resistance initially by the students. It was really like they didn’t want to think about that, they just wanted to discover what the hell their art was, first of all, rather than what it could do. And it felt, and I can understand this perfectly, it felt very forced to begin with. And I think that was the point that we also wanted to come up against as soon as possible. I mean the first assignments that we set them were first of all, make a performance for one person that will change their life. And the second assignment was, make a performance that will reach at least 500 people. And that was just within the first two weeks. So it was like, you know, we threw them in at the deep end. It was as much research for us as it was significant collision for anyone.

Since that whole block… One of the things that we did that was sort of last-minute, this was half-way through the block and it was sort of a shake-up, there was an activist who was going to come in and talk to them, the brilliant Shawn Devlin, he was coming in and we suddenly realized that we were still being a little careful in terms of our approach to public space, and I remembered this instance where I had been suddenly in a position where I had to shout my head off in an art gallery. Because it was being used as a sort of white-wash for a company that was busy dropping toxic waste around the capitol of the Ivory Coast. And they were using this very big art opening as a kind of public relations exercise. And myself and my partner, we handed out little fliers informing people to that effect, and we were found out, and I was bundled out by security. And as I was being bundled out, I yelled at the top of my voice to everybody pretty much what was on the pieces of paper that we were handing out. And that was such a liberating experience, it was extraordinary. I was bundled out, and that was it, and then I sort of felt wow, something switched inside me at that point. And so I told everybody in the block, the assignment was to go out and shout in public space without being aggressive. That’s what we set for them. And so they did that and it was an interesting exercise to be at risk somehow, immediately. People were faced with something that was not a simple screaming of a position or some kind of a position, rather almost like a process of thinking aloud, or something that required the support of a public ear.

Such that you’re essentially trusting the public realm to listen intelligently to you. And with that trust, immediately changing the world around you, with that assumption.

This was all slightly on the back of the Lest We See Where We Are project, which in its second half involved standing in public space holding a large portable stereo which seemed to be amplifying a voice trying to think out loud about the future; and that by holding it, you’re somehow responsible for it. This was just a very complete audio illusion though, no-one else could hear it but you. Here though, they’re doing it for real. Edit and I later turned that into a dedicated workshop: Raising Voice in Public Space.

Just with this recent piece (Someone Else)… My work is sort of going away from just the instructions, the instructional thing, and into something more like assignments. I’m interested in that. How the assignment to go out into the city and try to strike up a conversation with someone who you wouldn’t normally get to speak to. Not just a random person, it’s not like you are just gonna go and use the randomness of the public realm as a way of getting your kicks or something. More, first of all, to create a space of reflection. Like who, in what way, is actually missing in terms of your interaction with the city. For me, it was I realized that I just didn’t know anyone from the Muslim world where I was living in London. And, just sort of shortcutting that for a moment, just pushing through one of those panels and discovering that it’s not that thick after all. It takes a little courage, but that courage, that being at risk, is so hard-wired into the idea of performance. I mean, I’ve learned that people like a dare in a way, they like to be at risk in that sense, through the autotheatre stuff. So it makes sense to make these assignments. They’re very careful, very carefully written assignments. The wording is extremely important. And in that way it probably is bringing me back to some of that Fluxus stuff as well. Because it is, on the one hand it’s kind of less precise than the sort of micro-managed instructions of the autotheatre. But on the other hand it is very authored still. It’s like a score in that sense. It’s a score for thought.

BG Whereas the earlier pieces have this emotional choreography, this is more of a social choreography.

AH Right. It invites a certain path through thinking. So first you have to think through in your own way and in your own time who that person might be that you might want to go up to, what kind of person that might be, maybe. And then you actually have to do it. And at that point, it’s actually pretty precise. I don’t only give them the line they can use if they want, I actually engrave it into the building as well. That was important for me, to make it as solid at possible. In retrospect, it’s funny, it reminds me a little bit of Moses with the tablets. Thou shall go out into the city and speak to someone you normally wouldn’t speak to. (Laughs)

One last note from Ant on The Extra People (via his blog):

I’m so lucky to have shown a lot of work in the States over these last years. After the early shows with curated guest performers – eg, Doublethink (2007 at PS122) – things took a turn for the micro, and for several years my work was better known for its intimate and reciprocal nature (Etiquette, GuruGuru, Cue China, The Quiet Volume). As many of you will know, these Autoteatro works (with different collaborators) have almost always been exploring live performance which is also automatic, and unpeopled beyond an unrehearsed audience.

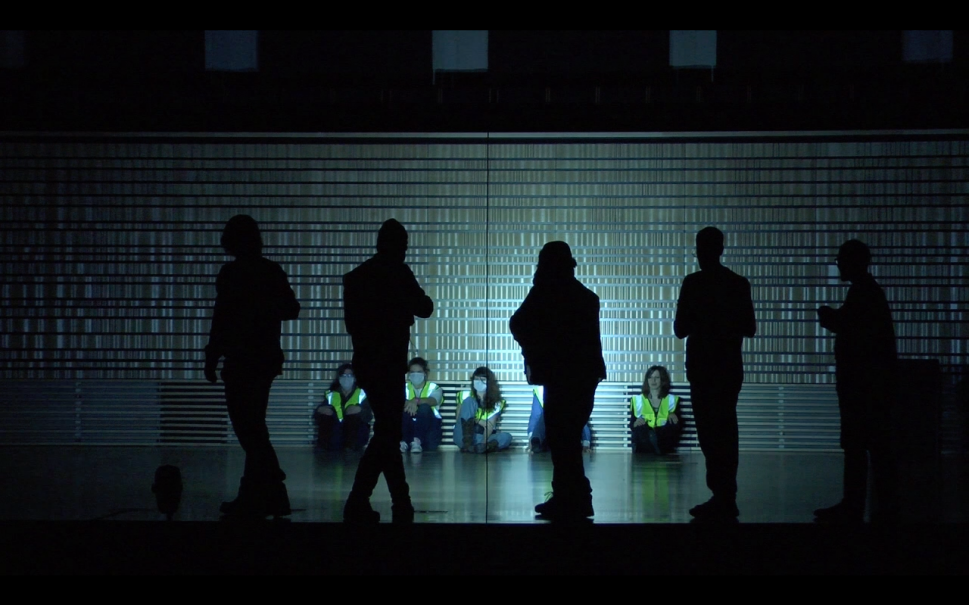

The Extra People continues the same thread, but brings it back into the theatre building and its scale. The system however (present as a synthesized child’s voice) seems not to know what a theatre is, or what it’s for. We don’t use the building’s lights or sound – it’s all in the headphones, and in your hands (powerful LED flashlights). You’re given a high-visibility vest, and you’re cast as an Extra. But for what?

“The overall picture is out of your reach: too big, beyond your comprehension or simply not your job to know. With hints of today’s fast-developing “voice-directed” warehouse management systems, the child voice leads you through the cracked dreams of today’s temporary, ‘flexible’, high-viz and debt-ridden worker. Highly realistic binaural recordings lend this stark zone, somewhere between Beckett and Ballard, a hallucinatory edge: an audio landscape so real and complete that at times you may mistrust your eyes. Public-private divisions are also messed with: the voice reverberates off the walls of the auditorium – and yet not-one else can hear it.

In a challenge to the assumption (often taken for granted) that collectivity is what you find in the theatre, the building here reflects society rather differently, with its audience situated as atomised individuals adrift or even asleep among both seating and stage; plugged into their own audio streams, patiently awaiting their call, and eventually acting upon it. And all the while the fabric of their realities disintegrates until the proceedings on stage resemble, from within, a looping, dementia-ridden process, where roles of attendant and dependent rise to the surface, before switching as easily as the flashlights changing hands. An initial sense of exposure is slowly overcome by one of oblivion until the memory of what it was like to sit quietly with critical distance seems as far away as the seats – somewhere out there in the dark.”

interview and additional text by Ben Gansky

all photos courtesy of Ant Hampton’s website except where noted